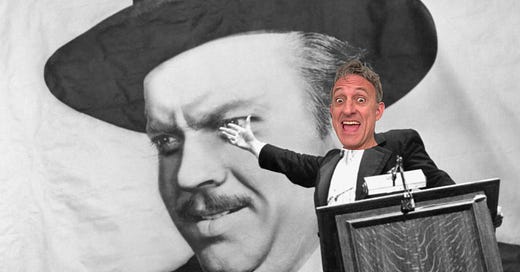

Your Stories Should Raise Questions - Citizen Kane meets The Oscar Project

Rosebud, Raising Questions and How to Put Words on the Page

I’m here to provide value to storytellers and story lovers who are living—or will live—on this planet. I’m less concerned with dead people at this time.

While I get personal pleasure from The Oscar Project’s hook—this guy is gonna watch all 85 films that have won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay—I’m more interested in using these films as windows into powerful storytelling so we can learn from stories that have received the highest honor for original writing in film.

With Citizen Kane, I’ll explore the practice of Raising Questions in narratives, and I’ll flex my audacity by rewriting a bit of the script to show readers how to make their own screenplays more readable, more filmic, and more delicious to producers, directors, actors, and other collaborators.

Citizen Kane

Citizen Kane has been the subject of hundreds of books and thousands of articles over the years. Full Disclosure: I didn’t actually count. But a quick look revealed everything from academic studies on its cinematography and narrative structure to biographies of Orson Welles that explore its creation. Not to mention the endless pop culture references to Rosebud, possibly the most known word in cinema history. It begs the question: What’s the big fucking deal?

After watching the film with all my attention and thinking about through the lens of storytelling, I get it. I get it and I love it.

A.I. & Me

As a reader-supported publication, I simply don’t have time to write original, quippy summaries about all the films and their place in history. I look to the cyborg class for assistance and then tweak from there. And so…

Citizen Kane is one of the most influential films in cinema history, often hailed as the greatest ever made. Written by Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles, the film shattered conventions with its non-linear storytelling, deep-focus cinematography, and bold use of sound. Beyond its technical innovations, Kane endures because it’s a sharp, haunting study of power, loneliness, and the way a man’s life can be distorted by the myths he creates around himself. Decades later, filmmakers are still borrowing from it, critics are still debating it, and audiences are still drawn to the mystery of Rosebud.

The screenplay is credited to Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Wells although there is controversy around that. I haven’t yet seen the David Fincher film Mank (2020) but it dives into the debated authorship of Citizen Kane, focusing on screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz’s role in crafting the script. The film portrays Mankiewicz as the true creative force behind Kane, emphasizing his wit, political cynicism, and personal experiences that shaped the story, while downplaying Welles’ contributions. After freshly watching Citizen Kane, I’m excited to watch Mank which was based on a screenplay written by Fincher’s very own father, Jack Fincher.

.

Kane v. Trump

For crying out loud, my intention here is not to connect every film to our current politics—let alone to the guy in the White House who’s gonna huff and puff and then blow it all down. But I’m quickly realizing how naive that thought is; if art aspires to communicate any kind of truth then it is inherently political, especially now, when the very concept of truth is at the center of cultural conversation.

In writing about The Great McGinty, it was impossible not to reference Tr#mp, given how McGinty rises through politics as a corrupt outsider, and with Citizen Kane, I would be willfully blind not to acknowledge the parallels between these two men: one fictional, and one who acts as if he is.

It shouldn’t surprise me that a film about an infamous, powerful newspaper mogul—Charles Foster Kane—would have parallels to our current president, a master of media manipulation. But watching it in 2025, nearly every sequence felt deeply resonant and relevant, reflecting the life and times of Donald Trump in ways I couldn’t ignore.

Kane and Trump are both larger-than-life figures who understand that truth and reality can be framed, packaged, and sold. Both built their identities on wealth, power, and an insatiable need for attention. They both use the media as a sword to attack others and a shield to protect themselves.

Kane, through his newspaper empire, dictates what people should believe: "If the headline is big enough, it makes the news big enough." Trump uses a relentless barrage of tweets and blather to shape public opinion: "If you say something and keep saying it, they will start to believe it."

They manufacture conflicts, shift blame, and rewrite history as needed. And beneath it all, they share the same fundamental insecurity: a desperate hunger for validation that no amount of headlines or applause can ever satisfy. Even Kane’s palatial estate, Xanadus, is in Florida!

The parallels were so many, I found myself Googling Trump’s favorite movie, and sure enough, Citizen Kane was listed at the top across multiple sources. Honestly, I wouldn’t be shocked if Trump’s entire playbook was, in some way, informed by the film. If any of my readers have insight into this, drop it in the comments.

But I want to talk about writing so…

What’s the takeaway for writers in comparing these two men. For me, it comes down to having confidence in universal, archetypal themes. One reason Citizen Kane remains relevant is its focus on timeless themes of Power—and a protagonist secretly driven by Personal Loss.

We all have experience with power, and we’ve all faced personal loss so as you develop your stories, dig into your own relationship with these or other universal human experiences. Name them. Explore them. You’re bound to find something useful in there.

Raising Questions

When I’m cracking a story (or helping others crack theirs), I gravitate toward simple words. Instead of leaning on jargon or academic language designed for analyzing stories rather than creating them. I like timeless, undeniable words and phrases that land instantly.

We all know what a question is. We’ve asked them every day of our lives. No MFA required. No screenwriting book necessary. Any child understands what a question is—my seven-year-old asks approximately two per minute, which works out to 960 in an eight-hour day. (Some days are longer.) Hell, even dogs get it. We know because of how their little puddin’ heads react when we ask about walkies or cookies.

Rosebud…

Citizen Kane contains arguably the most famous question in film history: Who or what is Rosebud? The entire narrative hangs on that question as a reporter investigates Kane’s dying words.

"Rosebud" is introduced in the opening scene, and the mystery is resolved literally in the closing beats. Not every story can or should hang its entire narrative on a single essential question like this, but plenty of great ones do. Will Ahab find the white whale?Who is Keyser Söze in The Usual Suspects? Who the hell shot J.R.?

No matter the form, great storytellers Raise Questions throughout their stories. What the hell is going on with Silly Billy the clown in the 2003 documentary Capturing the Friedmans? Oedipus is who, now?! Even the loathsome predatory world of advertising (sorry, not sorry) has Got Milk? Where’s the Beef? What would you do for a goddamn Klondike bar? Questions are powerful tools to engage any audience.

Answering Questions

A writer can answer a narrative question at the end of a scene (What’s behind the filing cabinet in Being John Malkovich?), at the end of a sequence (Will Luke eat all 50 eggs?), or at the end of the story (What’s in the briefcase in Pulp Fiction?)

It sounds simple. And in some ways, it is. In other ways, it’s not. Welcome to the writing process. More specifically, I encourage writers with this phrase:

Raise questions the audience wants to know the answer to.

That’s the bigger, harder task that involves creating a world and characters compelling enough that we care about those questions in the first place.

PRO WRITING TIP:

Here’s one simple, actionable step to add to your writing process: at some point, step back and ask yourself: What are the narrative questions in my story? When do I answer them? Am I getting the most drama out of those questions and their answers?

A Perfect Scene

My favorite part of the script comes on pg 145-150 when his wife Susan leaves him broken and alone. A scene like this can serve as a North Star for a writer because it perfectly dramatizes the inner landscape that has been driving Kane all along.

After slapping her in the previous scene, he begs Susan not to leave. In a beautiful performance by Welles, you can see the deserted child who we met in the beginning of the film. And now, late in life, he is desperate not to be abandoned again. In screenplay language, the Inciting Incident was the moment he was taken away from his family and this All is Lost moment has him being abandoned and alone again. He is forever haunted by his childhood and cursed to repeat it.

As further proof, as he proceeds to tear apart the room, and I couldn’t help but see a child’s tantrum that has been waiting for his entire life. Afterward he picks up the snow globe and he says the magic word, “Rosebud” — a word rooted in his last happy childhood memory. Quite frankly it’s perfect.

I’ll be honest—I hadn’t seen this film in years and was half-asleep at the time, so despite its place in cinema history, I thought I might find it dated, tiresome, and/or slow. What a jackass thought that was. I absolutely loved the film and found myself riveted by some of the performances and scenes and practically breathless at how relevant it is today.

PRO WRITING TIP:

Are you haunted? Is there a secret or even just a sensation in your body that you've been carrying for years? Even if you weren’t taken from your parents at a young age by a wealthy banker in a smart hat, I’m sure you have your share of painful and complicated experiences. Name them. Explore them. Write about them.

A Note On Race

In The Great McGinty, the only people of color were a couple of servants; in Citizen Kane, the only Black face on screen belonged to a lounge singer. If you're feeling confused or exhausted by conversations about representation in media, take a moment to imagine children—yes, it’s about the children—growing up on stories where white people are consistently served or entertained by people of color. It’s not hard to see the problem.

As I continue The Oscar Project, I’ll do my best to track how representation in these films has evolved over the years. As a reader-supported platform, I welcome anyone who wants to contribute relevant insights—strength in numbers and all that.

On the Page!

For Paid Subscribers I’ve rewritten Citizen Kane. Okay, just a little. I wanted to illustrate ways to make your script more easy on the eyes, to read like a movie, and to make producers and agents like you.

There is more than one way to do this. I took a stab to show the benefits of including White Space and eliminated the references to camera because I imagined this being written by someone who is not going to direct it but also because standard practice generally deemphasizes including camera references. You’ll find the whole Kane script here too.

Revising Kane

37.3KB ∙ PDF file

Citizen Kane Script

219KB ∙ PDF file