How To Craft A Character Arc with Stars in Your Eyes

Learning Story From Oscar Winning Writers in The Oscar Project

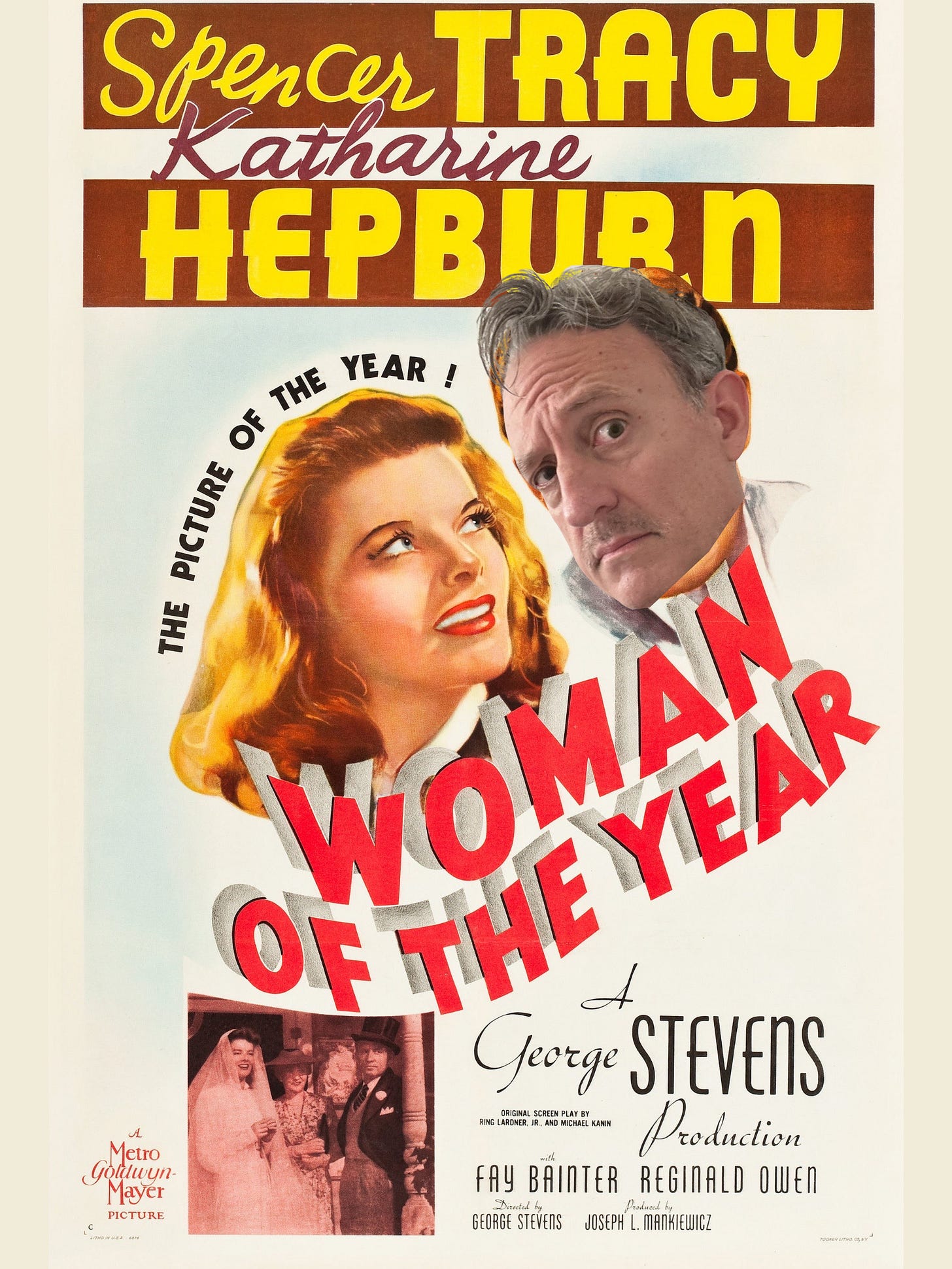

Well, it’s happened. Like a starry-eyed Spencer Tracy, I have fallen in love with Katharine Hepburn. What a fool I’ve been for taking so long.

Until now, my celebrity crushes have been pretty specific. There was Kristy McNichol, of course, and then then there was Goldie Hawn in Private Benjamin, Bernadette Peters in The Jerk; Terri Garr in every Letterman appearance ever, and Julia Louise Dreyfus and that’s it. Okay, also Gillian Anderson from the moment I saw her without her Scully hair. And now there’s Katharine Hepburn as Tess in Woman of the Year. Her performance was utterly captivating. Spencer Tracy was undeniable as well as he managed to portray a man with vulnerability and emotional needs despite it being 1942. But we’re here for the writing.

The Oscar Project

You don’t have to be a screenwriter or filmmaker to be starry-eyed about The Oscar Project. To me, writing is writing and storytelling is storytelling so any writer or storyteller will benefit from the story tools and techniques I pull from these films. And if you’re simply a lover of cinema, you might find yourself appreciating these films on a new level after revisiting them with me. Or perhaps you’ll leave a cranky comment.

SUMMARY BY ME AND AI

Woman of the Year is a romantic comedy directed by George Stevens and written by Ring Lardner Jr. and Michael Kanin with uncredited work on the rewritten ending by John Lee Mahin. The film stars Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy in the lead roles, with Hepburn portraying Tess Harding, a successful and independent political columnist, and Tracy playing Sam Craig, a sportswriter who is her more grounded, traditional husband. The film explores the tensions in their relationship as Tess’s career and ambitious nature clash with Sam’s more down-to-earth lifestyle, offering a witty examination of gender roles and marriage in post-World War II America.

The film was a critical and commercial success and marked the beginning of the iconic pairing of Hepburn and Tracy. The film won an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, awarded to Ring Lardner Jr. and Michael Kanin. Hepburn received widespread praise for her portrayal of Tess, cementing her status as one of Hollywood's top stars. The film remains an enduring classic for its sharp dialogue, memorable performances, and exploration of social issues that are literally in the headlines of today.

Bending Gender

What surprised me most about the film was how sophisticated, subtle, and emotionally honest its view of gender roles turned out to be. It’s not what I expected from a movie made in 1942. But it shouldn’t have surprised me — know your history, Bill Gullo!

After all, that was a time when gender roles were upended as American women stepped into new roles because men around the world were brutally killing each other. Rosie the Riveter emerged that very year (I looked it up) so a movie from that time should have an interesting take on gender.

To be honest, after initially being impressed by the gender dynamics of the film, I found myself newly disappointed that our country still suffers from so many gender-based problems. My very unscientific research confirmed my vague assumption: women still make about 85% of what men make for doing the same job. Revisiting the iconic Rosie posters made me imagine a transformative trans Rosie moment.

The story is grounded in Sam’s very reasonable desire to bond with Tess after they marry. He’s not a neanderthal barking orders or expecting to be waited on. In fact, he’s deeply drawn to her intelligence and independence, and I thought the writers gave him a sweet and surprising vulnerability.

What he craves are small, human things: notice my new hat, think of meeting me in Chicago. He wants to feel loved. To use a contemporary phrase: he wants to feel seen. Maybe I’m biased as a ‘sensitive man’, but I found he expressed these needs in a way that felt honest and vulnerable but never needy or desperate.

Don’t get me wrong—it’s not perfect, especially through the lens of today’s understanding of gender as a social construct. And the film could have gone further with the topic, but they rewrote the ending to include a clunky backwards step. Regardless, you’ll see film critic Stephanie Zacharek was also impressed with the gender dynamics for most of the film.

“Until that final scene, the modernity of Woman of the Year is breathtaking, exhilarating, almost too bold to be believed in the way it outlines a path toward equality, and some modicum of peace, between the sexes. But that modernity, it turns out, was an elastic pulled too far. It had to snap back. Michael Kanin and Lardner had originally written a different ending, one that was actually filmed… Audiences at an early test screening seemed to like the film well enough—except for that ending, which baffled them, or perhaps just didn’t give them enough. Mankiewicz and Mayer, sensing imminent disaster, enlisted screenwriter John Lee Mahin to come up with some new dialogue.”

We interrupt this episode of The Oscar Project…

Thank you so much for reading this publication. At this stage of evolution, it would mean the world to me if you invited friends to check out what I’m doing here with The Oscar Project and upcoming In Person Meet Ups. I’m confident they’ll appreciate the recommendation, and if you refer friends, you’ll receive a Free Upgraded Subscription in addition to the good karma that comes with spreading news of a joyful thing.

How to participate

1. Share Storytellers Social Club. When you use the referral link below, or the “Share” button on any post, you'll get credit for any new subscribers. Simply send the link in a text, email, or share it on social media with friends.

2. Earn benefits. When friends use your referral link to subscribe (free or paid), you’ll receive a free upgrade that enable you to fully engage with Storytellers Social Club.

Get a 1 month comp for 3 referrals

Get a 3 month comp for 5 referrals

Get a 6 month comp for 15 referrals

Thank you for helping me to spread the word and the words!

And Now Back to The Show…

Character Arc & Escalation

I talk with many screenwriters who struggle with crafting a gradual, compelling character arc over the length of a feature film. So let’s use this film for that.

Broadly speaking, Sam’s arc moves from the assumption of a shared life with Tess to the painful understanding that she is unable — or unwilling — to truly integrate him into hers.

Early in the film, Sam agrees to move into Tess’s apartment despite his stated desire to buy a new home together — an early Breadcrumb on this Arc. Once there, he begins to feel increasingly marginalized in a variety of ways. At one point he’s told, not asked, to cook for her and her assistant, and he finds himself answering her phone calls when she’s too busy with other conversations.

“Big deal!” you shout at me, Bill Gullo. “Women have been cooking and answering phones for men since fire and phones were invented!”

True, and the script itself doesn’t treat these moments as a big deal. That’s my point with regard to crafting a Character Arc. The writers and director Stevens, and Tracy treat these moments as minor annoyances — the type most partners feel to this day. But those annoyances Escalate.

Pro Tip: When crafting your Character Arc include the tool of Escalation. In other words, the early points of conflict and friction should be smaller than those later in the story.

In Woman of the Year, the early moments of discomfort come from things like Tess thoughtlessly inviting people into their home on their wedding night or failing to notice that Sam bought a new hat. As a matter of fact, the hat scene is perhaps my favorite in the film. I loved seeing a leading man like Spencer Tracy showing earnest vulnerability around his wife not noticing his new hat. It wasn’t clownish or broad; it was simply a human being wanting to be noticed by the person he loves. Sound familiar to you in your life? It could be from your family member or a romantic partner, but that’s some Universal stuff.

Pro Tip: put your own specific Emotional Hot Spots into your characters. You are not the only one that feels that way so you’re bound to connect with readers when you bake such details into your stories.

As the story unfolds, Tess’s thoughtlessness escalates dramatically until she surprises Sam by bringing a refugee child into their home without consulting him. This scene competes as my favorite because I truly had no idea it was coming, and there’s a wonderful Red Herring right before the Reveal.

“Wait,” you should at me, Bill Gullo, “Why should a woman have to ask her husband’s permission for anything?!”

If you’re asking that, I have to assume your partner is miserable or non existent. The film does an excellent job of illustrating a fundamental human truth: everyone has an emotional need to feel valued by the people they love. If you argue that it’s acceptable to bring a child into your shared home without discussing it with your partner, please let me know in the comments. I’ll refer you to a couples therapist or a divorce lawyer.

Tess’s increasing disregard for him gradually pisses him off until her disregard for the child puts him over the top and turns the movie in a different direction. Ultimately, he comes to the painful realization that she doesn’t respect him or see him as an equal partner.

Pro Tip: when you have a big moment like the reveal of the refugee child, grab hold of it as a Structural Turning Point that you can build to and then come down from.

OPENINGS & ESTABLISHING

It’s easy for a book on screenwriting or a professor or a Substack writer with access to AI to tell you that Opening Scenes are important, but let’s get specific.

Woman of the Year opens with the ol’ newspaper montage that ends with dueling headlines: Tess’s reads “HITLER WILL LOSE,” while Sam’s declares “YANKEES WON’T LOSE.” In this brief moment of visual storytelling, we understand the core character difference at play. Tess is focused on global issues and conflicts; Sam is focused on sports—more local passions and everyday concerns. No lengthy exposition required. The headlines establish their dynamic and foreshadow the tension that drives the story. Plus it’s a small joke which signals the comedic Tone of the piece.

While the swirling newspapers belong to the old days, the intention behind them remains just as relevant today: the need to efficiently establish your story and your characters. I say need, but let me be clear—you can do whatever the hell you want. But if you’re hoping to introduce your work to people who don’t already know your brilliance—whether that’s producers, agents, competition judges, or program readers—I advise you to be brutally efficient without sacrificing your style.

I read plenty of scripts that spend ten pages establishing what they could do in one shot. I’m not telling you to put swirling newspaper headlines on page one but I am suggesting you find creative ways to establish your character and world and central conflict early.

Every scene matters. Not just because every page costs money in production, but because the people reading your script are looking for a compelling, propulsive experience. They want to keep turning pages. And if you fill your script with scenes that drift—people gazing out of windows, recounting their entire life stories without a clear purpose—you’re not giving them that. So be ruthless in your choices. Make every scene count. “Use your ink well,” is what I say to remind myself of being efficient on the page.

Their Headlines / Our Headlines

The Oscar Project films continue to resist my attempts to ignore the politics of our time. In The Great McGinty, Citizen Kane, and now Woman of the Year, there are themes and subtext that are immediately relevant today.

In one scene, Tess speaks powerfully about women’s rights and the journey to acquire more rights and power in society. I felt some sadness during the scene because it felt like the same speech could be delivered today. My mind is fully boggled by the power the patriarchy still holds as women lose their reproductive rights and have their very right to vote threatened by the SAVE ACT.

From a writerly point of view, though, the writers include humor during the speech which frankly reminded me that progressives and activists benefit when they’re able to inject visceral humanity and a sense of humor in their messaging. Check out this two minute clip:

An even more specific and timely example comes when Tess has a conversation about…wait for it…TARIFFS.

“Tariffs have always been regarded as the historic fly in the ointment of American foreign policy. In ordinary times, internal conflict between domestic financial interests is unfortunate. In a national crisis, they may be fatal. Now that the problem of beef has been settled, we can only hope for a quick solution to all the other beefs that thwart our national unity.”

BROOKLYN MEET UP! April 30th 6-9pm

I’m actually doing it. I have the place and I’m sending invites to my beloved creative community that includes fiction writers, filmmakers, poets, producers, and video game makers and other things. I’m in the mood to build something and Storytellers Social Club is it. Space is very limited but let me know if you want to come.